Mmetụta gburugburu ebe obibi nke ọrụ ugbo anụmanụ

Mmetụta gburugburu ebe obibi nke ọrụ ugbo anụmanụ dịgasị iche n'ihi ọtụtụ ọrụ ụgbọ a n'eji gburugburu ụwa. N'agbanyeghị nke a, achọpụtala na ọrụ ụgbọ niile nwere mmetụta dịgasị iche iche na gburugburu ebe obibi rụọ n'ókè ụfọdụ. Ọrụ ugbo anụmanụ, ọkachasị Mmepụta anụ, nwere ike ịkpata mmetọ, ikuku n'ekpo ọkụ, ọnwụ nke ụdị dị iche iche, ọrịa, na oriri dị ukwuu nke ala, nri, na mmiri. A na-enweta anụ site na ụzọ dịgasị iche iche, gụnyere ọrụ ụgbọ, Ọrụ ugbo n'efu, mmepụta anụ ụlọ siri ike, na ọrụ ugbo. Ngalaba anụ ụlọ n'agụnyekwa ajị anụ, àkwá na mmepụta mmiri ara ehi, anụ ụlọ eji arụ Ịkụ ugbo, na ịzụ azụ.

Ọrụ ụgbọ anụmanụ bụ ihe dị mkpa n'enye aka na ikuku n'ekpo ọkụ. Ehi, atụrụ, na anụ ndị ọzọ n'eri nri n'agbari nri ha site na fermentation enteric, na burps ha bụ isi ihe n'eme ka ikuku methane si n'iji ala eme ihe, mgbanwe ala, na ọhịa. Tinyere methane na nitrous oxide sitere na nsị, nke a n'eme ka anụ ụlọ bụrụ isi iyi nke gas n'ekpo ọkụ site na ọrụ ụgbọ. Mbelata dị ịrịba ama n'ihe oriri anụ dị mkpa iji belata mgbanwe ịhụ igwe, ọkachasị ka ọnụ ọgụgụ mmadụ n'abawanye site na ijeri 2.3 site n'etiti narị afọ.[1][2]

Ọtụtụ nnyocha achọpụtala na mmụba nke oriri anụ n'ejikọta ugbụa na mmụwanye nke ọnụ ọgụgụ mmadụ na mmụcha nke ego onye ọ bụla ma ọ bụ GDP, ya mere, mmetụta gburugburu ebe obibi nke mmepụta anụ na oriri ga-abawanye ma ọ bụrụ na omume ugbu a gbanwere.[3][4][5][1]

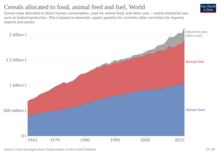

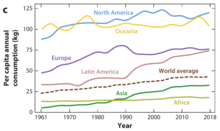

Mgbanwe na ọchịchọ maka anụ ga na-emepụta, si otú a n'agbanwe mmetụta gburugburu ebe obibi nke mmepụta anụ. E mere atụmatụ na oriri anụ zụrụ ụwa ọnụ nwere ike okpụkpụ abụọ site n'afọ 2000 ruo n'afọ 2050, nke kachasị n'ihi mmụba nke ọnụ ọgụgụ mmadụ n'ụwa, kamakwa n'akụkụ ụfọdụ n'ihi ịrị elu nke oriri anụ kwa onye (nke ọtụtụ n'ime mmụba oriri kwa onye n'eme na mba ndị n'emepe emepe). [6] A n'atụ anya na Ọnụ ọgụgụ mmadụ ga-eto rụọ ijeri 9 ka ọ na-erule n'afọ 2050, a n'atụkwa anya na mmepụta anụ ga-abawanye site na pasent 40.[7] Mmepụta zụrụ ụwa ọnụ na oriri nke anụ ọkụkọ anọwo n'eto n'oge na-adịbeghị anya na ihe karịrị 5% kwa afọ.[6] Nri anụ n'abawanye ka ndị mmadụ na mba n'aba ọgaranya.[8] Omume n'adịgasị iche n'etiti ngalaba anụ ụlọ. Dịka ọmụmaatụ, oriri ezì zụrụ ụwa ọnụ maka otu onye amụbaala n'oge n'adịbeghị anya (ihe fọrọ nke nta ka ọ bụrụ mgbanwe na oriri n'ime China), ebe oriri ezì kwa onye n'eri anụ n'ebelata.[6]

For every 100 kilograms of food made for humans from crops, 37 kilograms byproducts unsuitable for direct human consumption are generated. [9] Many countries then repurpose these human-inedible crop byproducts as livestock feed for cattle.[10] Raising animals for human consumption accounts for approximately 40% of total agricultural output in industrialized nations. Moreover, the efficiency of meat production varies depending on the specific production system, as well as the type of feed. It may require anywhere from 0.9 and 7.9 kilograms of grain to produce 1 kilogram of beef, between 0.1 to 4.3 kilograms of grain to produce 1 kilogram of pork, and 0 to 3.5 kilograms of grains to produce 1 kilogram of chicken.[11][12]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Carrington. "Huge reduction in meat-eating 'essential' to avoid climate breakdown", The Guardian, October 10, 2018. Retrieved on October 16, 2017. Kpọpụta njehie: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Carrington-2018" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Eisen (2022-02-01). "Rapid global phaseout of animal agriculture has the potential to stabilize greenhouse gas levels for 30 years and offset 68 percent of Templeeti:CO2 emissions this century" (in en). PLOS Climate 1 (2): e0000010. DOI:10.1371/journal.pclm.0000010. ISSN 2767-3200.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Parlasca (5 October 2022). "Meat Consumption and Sustainability". Annual Review of Resource Economics 14: 17–41. DOI:10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-032340. ISSN 1941-1340. Kpọpụta njehie: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-032340" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Devlin. "Rising global meat consumption 'will devastate environment'", The Guardian, July 19, 2018. Retrieved on July 21, 2018.

- ↑ Godfray (2018). "Meat consumption, health, and the environment". Science 361 (6399). DOI:10.1126/science.aam5324. PMID 30026199.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 FAO. 2006. World agriculture: towards 2030/2050. Prospects for food, nutrition, agriculture and major commodity groups. Interim report. Global Perspectives Unit, United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. 71 pp.

- ↑ Nibert (2011). "Origins and Consequences of the Animal Industrial Complex", in Steven Best: The Global Industrial Complex: Systems of Domination. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0739136980.

- ↑ Ritchie (2017-08-25). "Meat and Dairy Production". Our World in Data.

- ↑ Fadel (1999-06-30). "Quantitative analyses of selected plant by-product feedstuffs, a global perspective" (in en). Animal Feed Science and Technology 79 (4): 255–268. DOI:10.1016/S0377-8401(99)00031-0. ISSN 0377-8401.

- ↑ Schingoethe (1991-07-01). "Byproduct Feeds: Feed Analysis and Interpretation" (in en). Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 7 (2): 577–584. DOI:10.1016/S0749-0720(15)30787-8. ISSN 0749-0720. PMID 1654177.

- ↑ Mottet, A. (2022). More fuel for the food/feed debate. FAO.

- ↑ Mottet (2017-09-01). "Livestock: On our plates or eating at our table? A new analysis of the feed/food debate" (in en). Global Food Security 14: 1–8. DOI:10.1016/j.gfs.2017.01.001. ISSN 2211-9124.